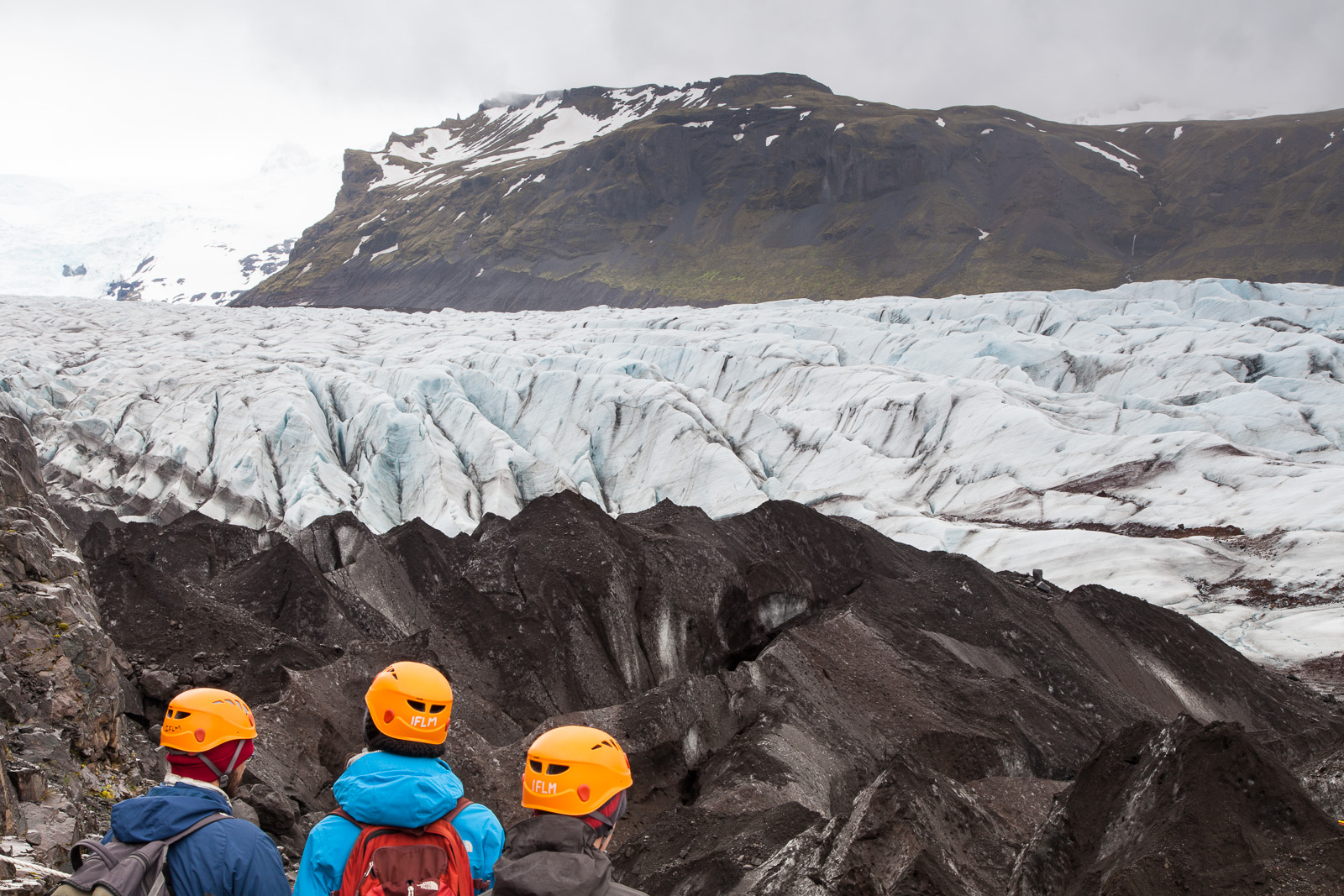

Just because I travel with the specific aim of photography doesn’t mean I don’t have fun And today’s image was definitely involved a lot of fun

One of the most visited spots along Iceland’s southern coast is the glacial lagoon of Jökulsárlón. Indeed, even at almost 400km from Reykjavik, there is a steady stream of tourists making the arduous coach trip out here and back in a single day which usually ends up as 9 hours in a coach and two to three hours at the lagoon. But despite what little time they get to spend around the lagoon they invariably leave impressed at what they have witnessed.As mentioned Jökulsárlón is a lake that has formed at the base of Vatnajökull – Europe’s largest glacier – and more specifically at the base of Breiðamerkurjökull, an outlet glacier. There are many complex processes linking these three entities but in essence Vatnajökull is highland ice cap where erosion, glacial motion, snow fall and gravity result in the edges of the ice cap spilling downhill forming what are known as outlet glaciers or glacial tongues. Eventually the outlet glacier meets warm air, ground, or both and collapse under their own immense weight into icebergs – a process referred to as calving. But words and the science behind them are definitely nothing compared to the sight itself.

I can understand why Jökulsárlón is so popular – thousands of icebergs at the foot of an awe-inspiring glacier – I would have been awestruck too had I not been to Antarctica. Alas however, I have been and so, as impressive as the lagoon is, it left me a little, well, cold.

One of the interesting things about Jökulsárlón is that it vents out via a narrow estuary on to the very top of the North Atlantic and because of this there is a natural tide that pulls the icebergs out to sea. Get there early in the morning after low tide and you’ll be greeted with a sea full of icebergs. It is not a time to go for a swim – some of the larger icebergs can weigh upwards of a 100 tonnes but the power of the North Atlantic tosses them around as if they weighed nothing. The incoming tide also pushes some of the icebergs back onto the beach, grounding them on the black sand. It is truly stunning: A landscape of only black, blue and white. Alas, if you are taking a coach trip out of the capital, you won’t get to see this marvel of nature – as the waves beat rhythmically against the beach and the temperature rises, the mighty icebergs melt and by evening only small lumps remain, the largest the size of a pet dog.

I found myself on Jökulsárlón beach several times trying to do justice to what nature had designed. As can be seen from this image – and the rest in the gallery – the best angles are side on to the sea shooting along the beach. All well and good and I had even bought Wellington boots for this very purpose, which were 1100 miles away back in the UK as I couldn’t get everything into the suitcase! So I ended up playing chicken with the Atlantic: Set up the tripod just out of reach of the waves and begin the task of trying to capture the right shape of wave on the beach at the right time (which is tricky with multi-second exposures), all the while keeping an eye open on the waves coming in to the side of me. Of course, just as soon as I would get in to the swing of things, a rogue wave would come hurtling in and it would be a mad dash out of its path, often having to leave the camera behind perched on the tripod and hoping that there would be camera to return to. Over the course of my visits I discovered a list of handy tips, the hard way.

First, don’t set up the tripod with a thigh-high iceberg right behind you and between you and safety as, when an incoming wave means it time to make a dash for it, the iceberg is somewhat less bothered. You learn a lot about momentum, high centre of gravity, pivot points and just how big a bruise a iceberg can make by crashing full speed into one.

Second, just because you find a nice, solid feeling iceberg you can stand on to raise yourself above the level of the incoming wave, don’t get smug. Given a big enough wave that solid feeling iceberg suddenly becomes far less solid and the thing about ice is that it isn’t exactly a high friction surface.

Third, no matter how far up on the beach you leave your camera backpack out of harm’s way, it won’t be enough. The tide is coming in and you’re engrossed in trying to capture the perfect moment. You end up relying on the goodwill of others to either shout a warning that your backpack is about to get a good wash, or to move it for you.

Fourth, no matter how much you rinse the sand off your tripod after a session you’ll still take half the beach home with you. By the end of the trip my lovely carbon fibre Feisol was making alarming grating noises. Luckily John over at Feisol’s UK distributor was brilliant and had the tripod serviced and back in my hands within a week.

But the biggest thing I learned on my days to the beach was that, despite the bruises and the soaking wet feet, I was having more fun than I’d had in years.

Oh, and not to leave my wellingtons at home again…