With a long weekend here in the UK there’s been some time to look into some of the specifics for the Iceland road trip. Over the past few weeks I’ve spent a lot of time reading blogs on the Internet, seeing what people recommend, what problems they encountered and what hidden gems they found that might not be in the usual travel guides. Many hours of reading and note taking with Evernote has resulted in a lot of information that now has to be sorted into some kind of plan.

One of the nice things about urban photography is the your options are necessarily limited. Opening times dictate when you can get interior shots, built up areas dictate the angles you can shoot from and in metropolitan areas the times that see the highest population movements – rush hour – dictate at what times you can shoot if you want to capture a specific interaction between people and architecture. Another nice thing about urban photography is that things are usually quite close together.

Not so on a road trip. Of course it shouldn’t have come as a surprise to me – after all I’m circumnavigating a country – but it’s the little things that soon add up.

One of the places I’m off to is Dettifoss, a waterfall in the north-eastern part of Iceland. If you’ve seen the film Prometheus, its the one at the beginning of the film. Many sources state that it’s Europe’s largest waterfall (in volume of water, not height or width) and so for those who venture out of the capital Reykjavik it’s usually high up on the ‘Top 10’ list. Researching this apparently simple destination started out as straightforward, soon became confusing and finally ended up as my own personal Moby Dick. And here’s why.

Using Google very quickly showed that Dettifoss sits, roughly equidistant, between the self-drive tourist’s dream road, route 1 and the north-eastern spur, route 85. I already have plans to stay for a couple of nights just off route 85 and so it is a simple decision: wake up, check out head east of route 85 until the turning for Dettifoss. As it turns out, there are two roads leading to Dettifoss and that is where it all started to get complex.

Iceland has a three-tier road structure. In Reykjavik and other population centres they’re tarmac surfaces. This is also true of arterial roads such as route 1. The second tier are gravel roads – usually less frequently travelled roads although parts of route 1 are still gravel. Then there’s the F, or mountain roads. Perhaps less ‘road’ and more ‘track’ these are impassable during the winter months and suitable only for 4×4 vehicles the rest of the time. Many of the wonders of Iceland’s interior are only accessible via F roads.

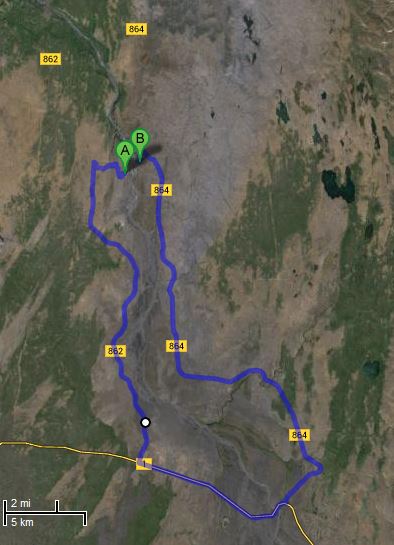

So, going back to Dettifoss. The two roads take you to the east and west banks and the bank you are standing on radically changes the view and the feel you will get. My first thought was “Duh! Just shoot from both banks” but this then highlighted the other issue when travelling through Iceland: There’s never a convenient bridge when you need one. With Dettifoss, to get from one bank to the other – a linear distance of approximately 120 metres, involves a 65km detour.

Things became confusing when I started to look at the roads themselves, something you need to do if you’re not in a 4×4. Originally the road leading to the west bank was classified as the F862 denoting it as unsuitable for non 4×4 vehicles. As a result the east road – the 864 – became the road of choice. It was still a track, but in much better shape than the F862. Then in 2010 the F862 was replaced with a paved route and it became simply the 862, instantly making it the better route to travel. As I read around on the Internet and at people’s experiences it was frequently not clear as to which version of the 864 they were referring as dates were missing, or they were writing after 2010 about a ‘previous’ trip etc.

After a few hours of searching around on the Internet in frustration I dropped an email over to Peter of the Iceland blog site Iceland24 (iceland24.blogspot.co.uk) asking him if he could clarify the current status of roads (F)862 and 864. I was impressed when, shortly over an hour later, a reply came back. I was seriously impressed when the reply was that there would be an article on the website dedicated to visiting Dettifoss – within the hour! Which there was. Looking around Iceland24 reveals a good amount of information for the visitor and Peter seems to be very approachable.

As mentioned above the other factor is the type of shot you want to get. If you are after the ‘Prometheus shot’ where the falls recess away into the frame, then you want the east bank. As the film shows, the east bank is a barren, rocky expanse and you get a clear view of the falls and, unobscured by mist, of the west bank, a green carpet of moss and plant life But, from the west bank, you have a completely different experience; the falls are face on to you dominating the frame with a wall of water. There’s plenty of mist in the air too and you’ll likely need lens wipes if you want a clear shot of the barren east bank.

If that were not enough to be contending with I also want to hike the kilometre or so up to Selfoss, a wide waterfall upstream of Dettifoss. But again, which bank would give the best shots?

And, of course, which bank is best for a dawn or dusk shot?

At some point over the past two days, it has become a mission and, much like Ahab’s quest of revenge on Moby Dick, I must work out the perfect combination of which bank at which time for which shot. I think I’m almost there…