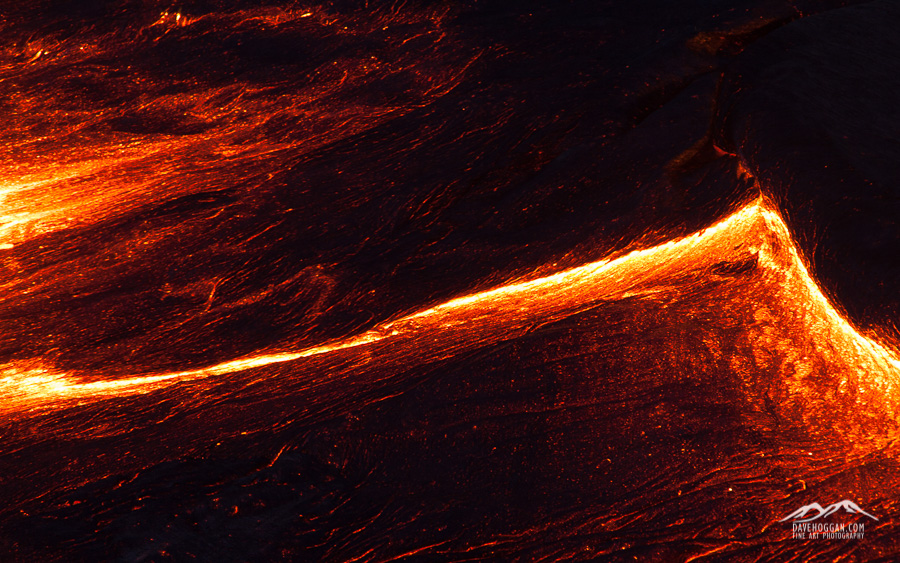

Despite my dubbing it “a big rock”, Spitzkoppe offers some beautiful scenery and one well worth spending time at.

Some things just take time, like this image taken at the Spitzkoppe range in Namibia.

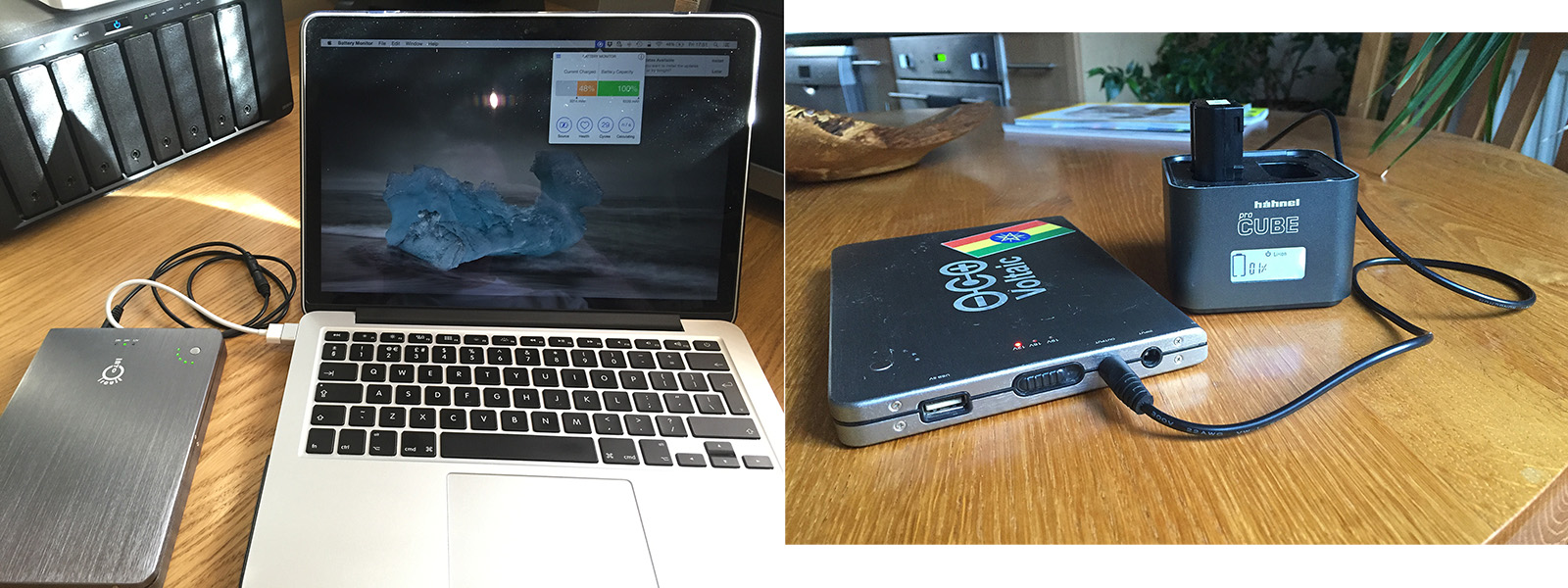

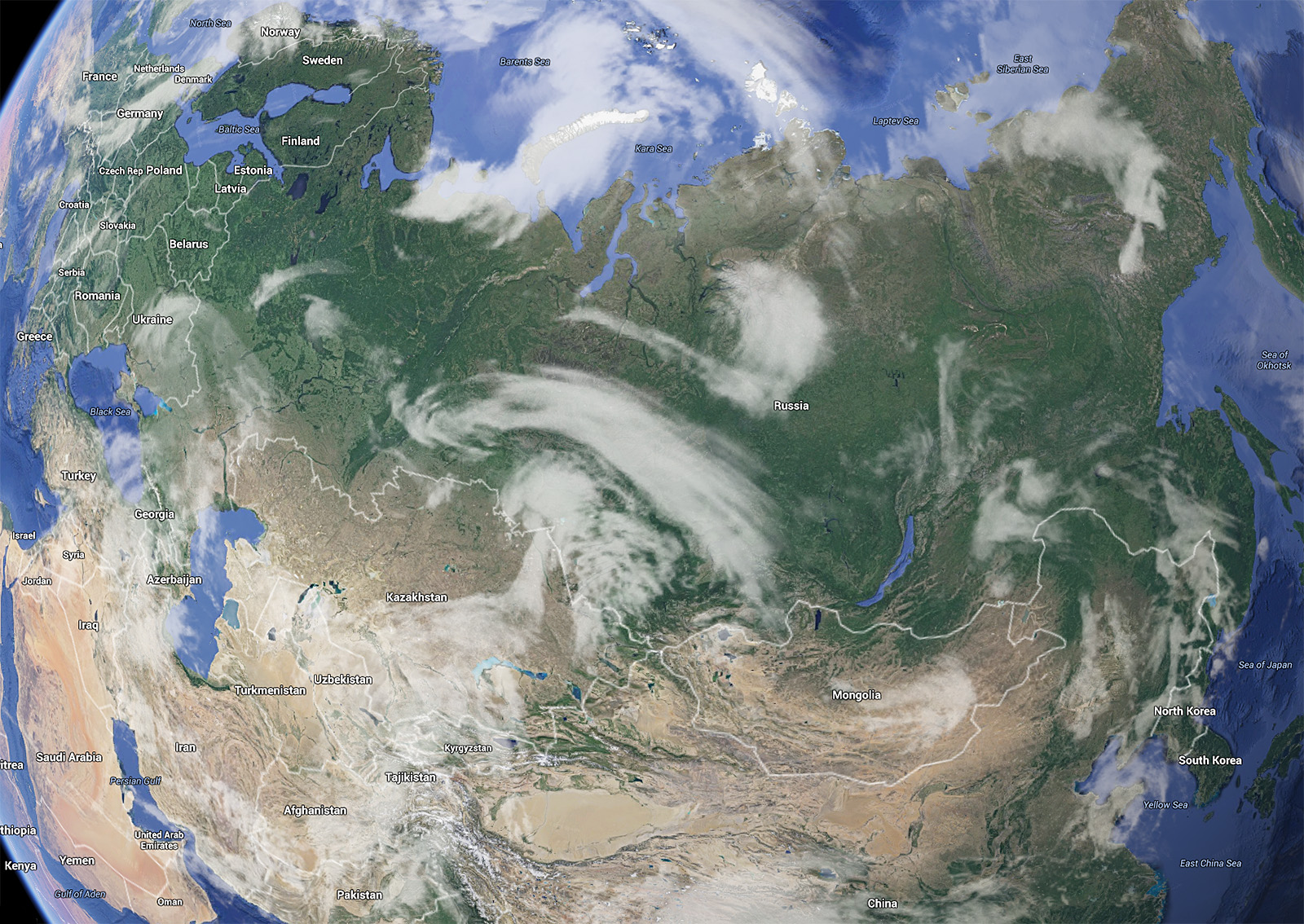

By the time we reached Spitzkoppe on our journey through Namibia we were finding our own feet when it came to understanding how to take night-sky images. Emil from Nature’s Light had patiently and repeatedly taken us through the process of capturing and subsequently processing images and we were finally getting to a place where we were less concerned about the process and more concerned about the composition. Even so, the first night we spent at the rock arch seen above was difficult for me.

I am not a fast photographer. As I look at a scene it takes time for the image to become clear in my mind. Until then all I see is a discordant jumble of elements all demanding attention. As so it was the first evening of shooting: the sky; the Milky Way; the arch; the boulders; the distant peaks. I spent a couple of hours shooting but left feeling deflated and frustrated.

The second day was spent doing not a lot of anything; the daytime temperature was creeping up to 40°C and the rock landscape was being bathed in harsh direct sunlight with no shade. But my mind was ticking over and as I worked through the previous night’s images I could see a shot in my mind. Spitzkoppe is a big landscape but using a wide focal length to fit it all in would reduce features to tiny dots. So a panorama might work. The problem with panoramas – especially at night – is that they take time to shoot and it was not until I started night-sky photography a few days previously that I realised just how quickly stars move. They’re surprisingly fast! The speed issue was compounded by the fact that I was trying to shoot the Milky Way and if I took too long shooting the individual images then the panorama would end up with the Milky Way in steps across the sky. The final challenge was that the moon was out in force and it would be all but impossible to stop it blowing the highlights sky high (yes, pun intended).

I like this image for a number of reasons. First it appeals to my inner geek as it is probably the most technically challenging shot I have taken consisting of several 30-second exposures whilst trying to keep foreground detail interesting and the Milky Way in one piece. Second, I like the repeated use of upward curves; the curve of the rock arch in disappearing off the top of the frame in the foreground; the curve of the secondary arch to the right; the curve of the Milky Way; the boulders in the mid-ground and curve of the mountains in the distance. And third, I like the fact that, if you look closely, you can see Emil and Romeo in the distance having a beer!

Photographs serve many different purposes from reporting events in a factual way to providing that 500pix “WOW” factor. I prefer those images that I find myself returning to time and again and igniting memories of spending time with kindred spirits under magical skies.