With the trip to Iceland being tomorrow and packing essentially complete I’m now at the point where I’m actually beginning to get excited. In fact there are only a few items left to deal with, including buying a few of those “meals in a bag” for the middle of the trip when I’m up in the Icelandic highlands and nowhere near a supermarket. That’s the double-edged nature of Iceland: It’s a truly breath-taking country but it favours the prepared.

Now, I do consider myself a reasonably prepared traveller, including the steps I take to stay out of trouble. But a recent post by a regular contributor over on the Trip Advisor Iceland forum did stop me in my tracks. In it she suggested that the profile for those travellers to Iceland that end up never leaving (alive) is male, a solo traveller, hiking and often with some experience. I fit 100% into that profile and whatever the source of this statistic I found myself double-checking my preparations for a “worst-case scenario”.

Risk analysts with tell you that there are three ways to deal with risk: Accept it and carry on (assume the risk), take steps to reduce the risk (mitigate the risk) or get someone else to handle the risk (transfer the risk). Depending upon the situation each option can be a valid approach, but in the case of my time in Iceland’s highland interior as the predictably unpredictable weather continues to worsen, option one would be plain, flat-out, stupid and option three (in this case meaning going on an organised trip) would be too expensive – if possible at all – and so inflexible as to render the reason for being there not worthwhile. So it was time to take the middle ground.

It is worth pointing out that there are usually three potential sources of danger in a given environment: From other humans, from animals and from nature itself. In Iceland you can disregard the first two completely. If anything is going to cause you problems, it will be the weather.

Staying on the Grid

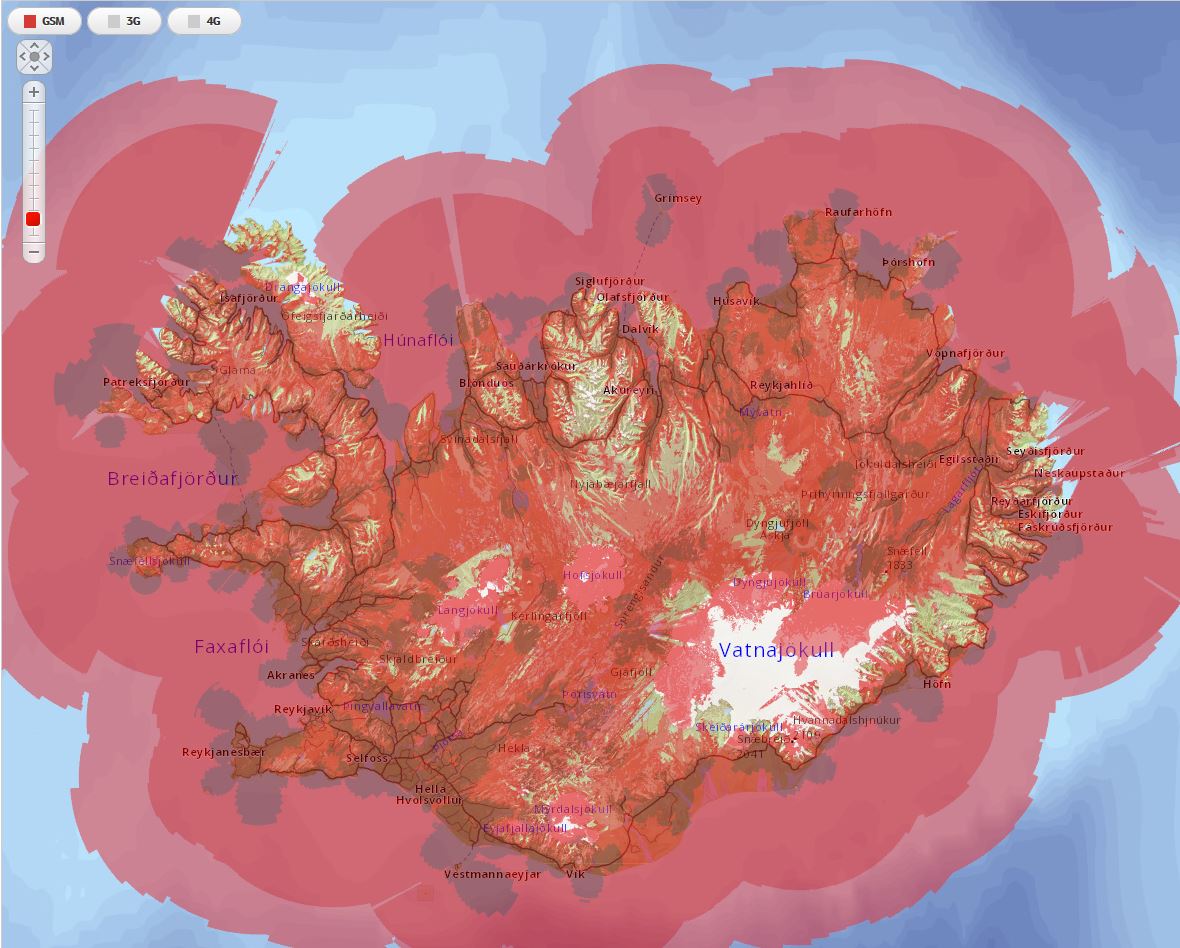

The first thing to mention is telecommunication. Iceland has excellent mobile phone coverage from a number of operators. For example, take a look at Vodafone Iceland’s GSM coverage:

So, should the worst happen I’m more than likely going to have access to the outside world, but who am I going to call?

Perhaps the obvious would be friends or family back home. If I had no other alternative then, well, I have no other alternative but I’m not going to be calling for a chat – I’m going to be having an emergency. If you’ve ever tried it trying to organise a rescue for someone from another country it is very difficult and as time is the enemy here, I really I don’t want to be in that position. So I’m making sure that I have the phone numbers for my accommodation in Iceland and confirming my arrival with each of them on the morning of arrival.

An example of why making sure that the accommodation knows you’re definitely arriving is useful happened to me back in 2010. We were taking a 4WD from the village of San Pedro de Atacama in northern Chile to the town of Uyuni in southern Bolivia. It’s a route taking three days and involves travelling through the northern Andes at an altitude of 4,500 metres. It’s a barren, unending wilderness where the temperature drops to -15°C or below once the sun goes down.

Due to contaminated fuel the fuel pump died stranding us on the second day. Despite having been told otherwise there was no radio to call for help – and mobile phones were definitely out – and it was only because we were on a route that other 4WD vehicles used that we were able to ask a passing driver to let people know we needed help once he arrived back in civilisation. Which he didn’t do.

Luckily the accommodation we were staying in that evening were expecting us and when we didn’t show up they contacted the company who had organised our arrival and help was sent overnight to look for us. It was an uncomfortable evening – and we missed out on seeing some spectacular sights due to the delay – but we were rescued because of the accommodation raising the alarm.

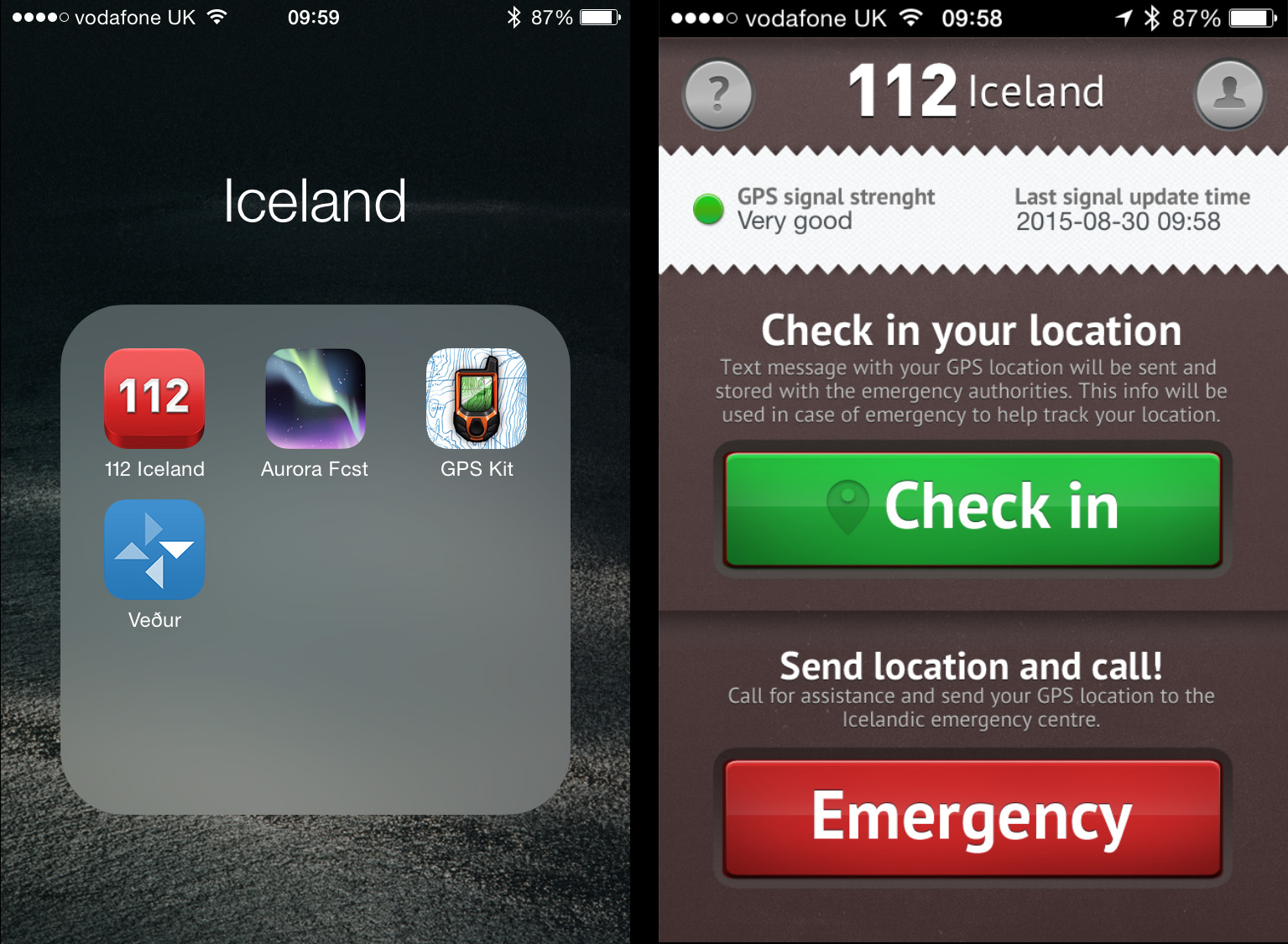

In Iceland you have other tools at your disposal. The completely free 112 app from safetravel.is and available for iOS, Android and Windows mobile devices allows you to keep in contact by letting the emergency services know your location. It’s simple to use and works by sending a SMS text message so doesn’t need 3G or 4G to operate, hence why I showed the GSM coverage map above – it’s all the app needs to work.

How you use it is up to you this but I just set my watch to remind me every 30 minutes to check-in. That way if the worst were to happen then the emergency services know my approximate location.

So, letting people know is very, very important and Iceland makes it so easy to do that there is no excuse not to do so. It is a zero-cost option for having someone looking out for me. I’d be stupid not to use it.

Of course, should I find myself needing assistance I’m likely going to have to wait until help arrives. For my trip I’ve considered three scenarios when travelling by myself: (1) The 4WD breaks down (2) I’m out hiking and the weather unexpectedly turns for the worse and I end up in a biting cold storm with very low visibility or (3) I sprain an ankle. Each of these conditions is quite possible and can be life-threatening if not prepared.

The “Car Breaks Down” Scenario

The ‘car breaks down’ scenario is a relatively easy one to deal with: Phone the car hire company. However, it may be that they cannot rescue me quickly and so I have to spend the night in the car. That’s where my trusty Alpkit SkyeHigh 600 sleeping back comes in. Rated down to -5°C it means that an evening stuck inside the car out of the wind and rain inside will also be a warm one and a break-down becomes an annoyance rather than dangerous.

The “Bad Weather” Scenario

Due to its geography and location the weather in Iceland can change exceptionally quickly, especially in the highlands, and so the best course of action is to assume the worst. For me this entails being out hiking in the highlands of Kerlingarfjoll and a sudden snow or rain storm comes in and reduces visibility to near zero.

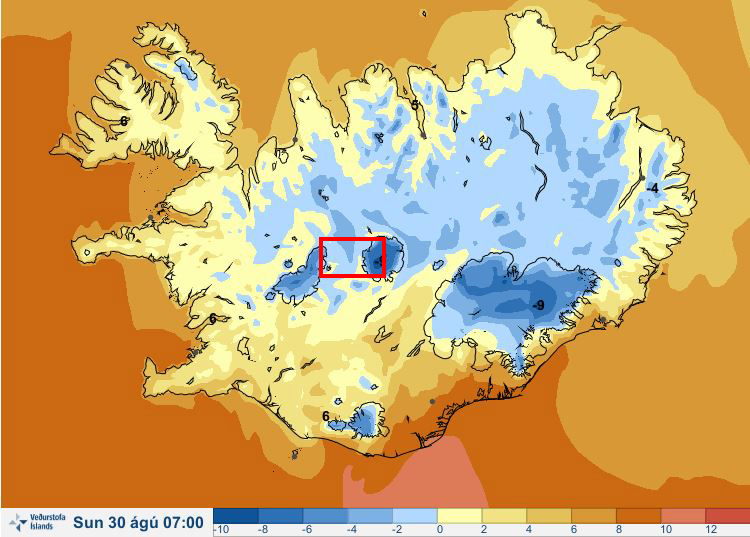

The first common-sense thing to do is check the weather forecast. It’s not accuracy that I’m after but rather a general idea and as can be seen in the above image from vedur.is – Iceland’s meteorological office – Kerlingarfjoll is going to be reaching sub-zero temperatures and so I need to ensure that I can keep warm and dry when out-and-about.

The easiest way to dress for the occasion is to use the layering principle of clothing (if you’ve not come across this then Google ‘layering principle clothing’). This is a tried-and-tested method of ensuring that your clothing suits your environment and in the highlands the outer waterproof and windproof layer is as important as the warmth-providing base and mid layers. Easy things to forget are gloves and some kind of hat.

I am pretty confident in my clothing and I’m happy that it will cope with the extremes of Iceland’s weather that I’ll be facing – it better as 66 North is an Icelandic outdoor brand – but I’m definitely following the advice of many experts who recommend avoiding jeans and cotton as, when wet, they don’t dry quickly and in a cold environment they can accelerate the cooling of your body and speed up the onset of hypothermia.

So, should the weather turn nasty, it won’t present an immediate danger and I’ll be warm and dry enough to get back to camp. Assuming I can find camp!

GPS used to be the tool of the seasoned outdoor adventurer but smart phones have put this powerful navigational tool into the hands of just about everybody. GPS apps are available for all brands of smart phone and, given that the software is cheap – and you can have a lot of fun later by downloading the data to your PC and showing your friends and family exactly where you hiked on Google Maps – it makes sense to invest in the app.

The display may look a little unfriendly but there are also options to download Google Maps data and use if when away from 3G/4G mobile coverage. You can then watch your route unfold as you walk.

I use an old iPhone 4S with no SIM card and running a dedicated GPS app – in this case GPS Kit. Other than the obvious ability to pinpoint my location it also has a tracking option that will allow me to backtrack without having to rely on visible clues such as path markers should I need to. The phone is in a rugged, waterproof case (by Lifeproof) that I picked up second-hand on eBay so there is no worry about using it in rain or snow. I’ve actually tested the waterproof nature having been diving with it to a depth of 12 metres so it doesn’t matter how bad the rain gets, it won’t be worse than that! I’ve also got a portable USB battery pack that is small enough to be easy to carry but can charge the iPhone twice over.

The “Injured” Scenario

The most likely form of injury when out hiking is a sprained ankle, especially when walking over uneven ground. Anyone who has had a sprained ankle will tell you how painful it can be, but when out-and-about by yourself it can be deadly. Back in 2008, when I was preparing to walk the wild section of the Great Wall of China, I relied a lot on the local knowledge of a photographer based out there and his advice as simple: Do not walk it alone. People have died after an injury and not being found for a couple of weeks. The good news is that in Iceland’s highlands you wouldn’t have to suffer that long – a night would probably be enough to finish you off.

There’s a reason that the “Wild Wall of China” is closed to hikers. This was a complete section until someone walked on it…

The single best piece of advice I have been given for hiking is to wear properly fitted walking boots that support your ankle. This does not necessarily mean the most expensive walking boots you can find – my current boots were significantly cheaper than all the others I was considering but they hold my feet securely. Looking where you are going and not rushing is good advice too. As my clothing is going to keep me warm and dry, I have no need to rush and anyway, having 10kg of camera gear to carry always slows you down.

No, should the weather turn nasty and visibility fail, the only thing that will likely kill me is panic.

But should it happen there are a number of tips for dealing with a sprained ankle and whilst I have a plan the simple fact of the matter is that the injury scenario is really one of those where my best hope of survival is the steps I will have already taken that day and outlined above. In the case of my stay at Kerlingarfjoll in the highlands my plan is simple:

- Each morning tell hotel the route I’m taking, when I expect to be back and that I will check in with reception on my return.

- I’ll also double-check the weather that day – local knowledge is always good.

- Use the 112 app.

- Use the GPS app to plot my route.

- Don’t rush and watch where I’m going.

Of course, I have my Icelandic “worst-case scenario” kit-bag (which is really just my usual travel kit with a dramatic name) which contains a few, cheap, lightweight items – along with a couple of larger items I use in photography.

- Strong painkillers

- Sprain bandage

- Spare bootlaces (handy for so many things, including boots!)

- Emergency stitches (also called suture strips)

- Liquid plaster (a paint-on anti-sceptic plaster)

- Plasters

- Compede (a UK brand of blister plaster)

- Scissors

- Tweezers

- Survival blanket

- Gaffer tape (carried due to its use for photography, but handy for splints)

- GPS

- USB power brick

- LED Torch (again, used for light painting in photography but has a 20 hour charge)

- Swiss Army Penknife (well, it’s not proper hiking without one!)

Despite seeming a large and costly list, the medical bits all fit into sunglasses case so really easy to carry around in a pocket or backpack.

At the end of the day you can never plan for every eventuality. What you can do is identify the potential dangers and plan as best you can around them. That’s usually the difference between trips that have “moments” that to tell your friends about for years afterwards and those trips that are your last.