It’s funny how time has a habit of passing by quicker than you would like, but the forthcoming expedition to the Danakil Depression in northeast Ethiopia has gone from being a comfortable 100 or so days distant to a more immediate 55 days with what I can only describe as alarming speed. So, it is time once again to start preparing for travel – assuming that I actually get there. After all, of all my trips, the expedition to northern Ethiopia represents the biggest gamble to date and there are many reasons why I might not be going.

The first of these is the kill date; the date before which I can cancel the trip without loosing the full cost of the whole adventure. Cancelling before this date means that I will lose the cost of the return flight to Addis Ababa and the deposit paid to Volcano Discovery. The kill date is really only a formality as I’m beginning to feel the excitement growing, but it does mark a symbolic milestone: Once the kill date has been passed, well, then I will really feel like I am going!

That being said, even once the kill date has been passed there are external issues that an cause the trip to be cancelled. The first of these is political or military unrest. As mentioned in a previous blog post the north of Ethiopia isn’t considered a particularly safe place to travel by many Western governments and the UK government’s advice is still “no travel for any reason”. The Danakil Depression, and the ghost town of Dallol is about as north as you can go before ending up in the middle of nowhere. It may still be a barren, desolate wilderness, but at least it is a barren, desolate wilderness with a name. The northern edge of Ethiopia borders Eritrea and it is this hotly contested border that causes foreign governments concern for those traveling to the area. We’ll be within 8km of the border and so, should anything flare up, we’ll be right in the hot seat. But, right now the situation appears to be calm and aside from an incident in 2012, no hostilities are being reported. In any event we’ll have a military escort.

The second issue that may arise is the ongoing spread of Ebola. What started as a surprising, but low-level outbreak a few months ago in Western Africa has been slowly spreading with cases arising internationally. A casual glance at a map show that Africa is a vast continent, but some would worry about going anywhere on the same continent during an outbreak. In this case however, I’m not really that concerned; Not only is there a large distance between the ‘hot-zones’ of Liberia and Sierra Leone in the far west and where I’ll be in East Africa, but Ebola is spread through human contact – specifically through coming into contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person. As mentioned above, the Danakil Depression isn’t exactly a popular spot to go to – one person going so far as to describe it, somewhat un-euphemistically as the “arse end of nowhere” and so I’m very unlikely to meet anyone who would pose a risk. No, in many ways I would be more concerned about contracting Ebola in London than I would in Dallol or its surroundings.

Of course the sensible thing to do when booking any trip – let alone an expensive expedition – is to ensure that you have proper and adequate travel insurance. Many people have travel insurance as part of their financial package with their bank and this provides a sensible level of cover for the basics – limited illness cover, loss/theft of possessions, cancellation of the trip by either yourself (due to family emergency, for example) or cancellation by the trip operator. I’ve used this kind of policy many times.

For some destinations, such as Antarctica, I needed some additional insurance to cover the cost of repatriation should I have become so ill that I needed to be airlifted back to the UK, but again this type of insurance is readily available as so many people these days go on skiing or other ‘adventure’ holidays. In fact such travel is so commonplace that it is not even that expensive to buy this additional cover any more. No, travel insurance is easy and affordable.

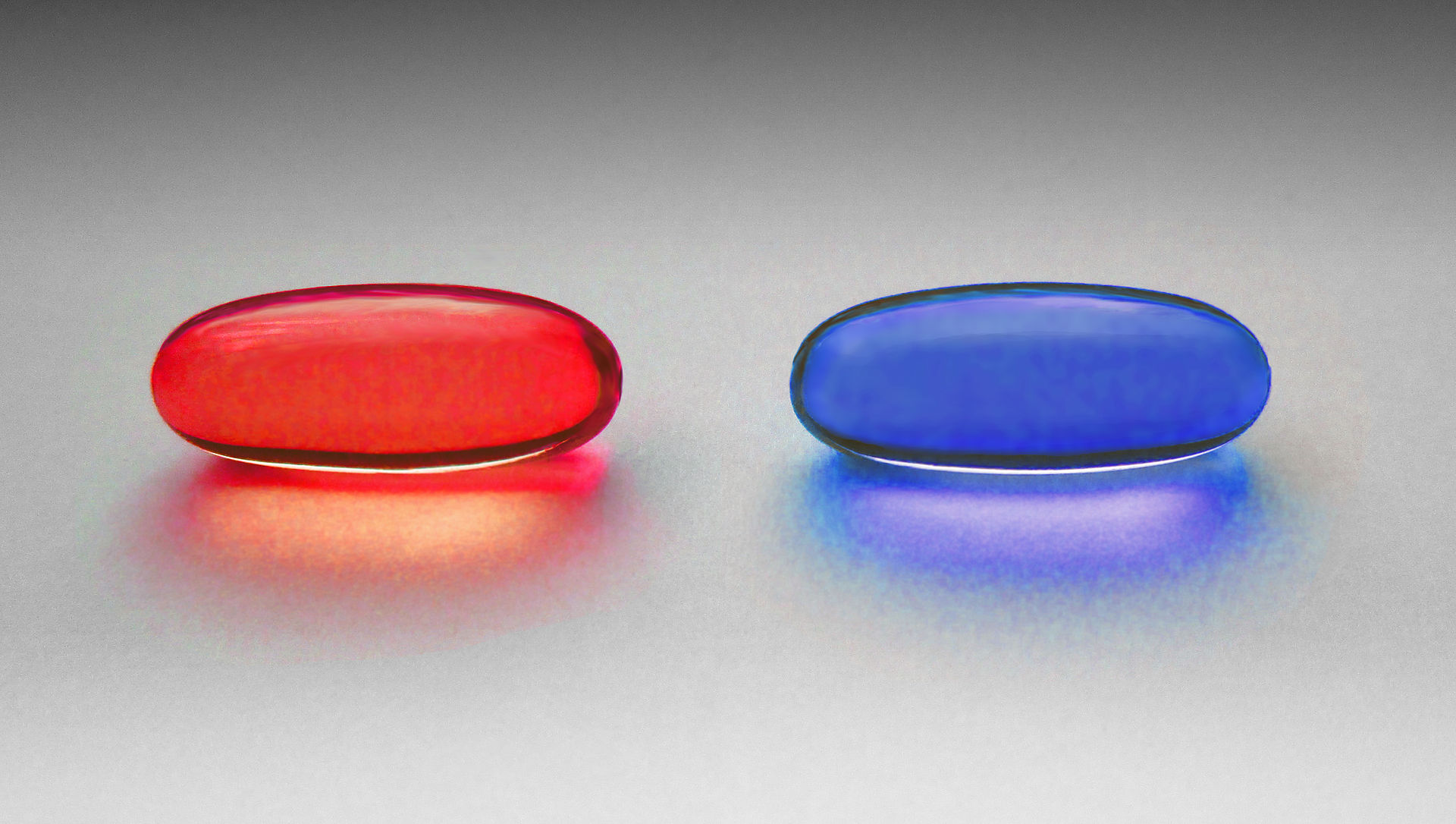

As with Neo’s choice in The Matrix, we can all choose to see beyond the daily World in which we live and beyond into the unknown. But, as with any journey, there are risks…

So why is this all such a gamble?

Simply put, all travel insurance policies in the UK have one fundamental requirement: That the destination that you are travelling to is assessed by the UK government’s Foreign & Commonwealth Office to be safe to travel to. If the FCO recommends against travel and you go anyway, then the policy is null and void. So given the FCO’s ongoing recommendation for northern Ethiopia, no UK insurance policy will cover me.

Now, you would be insane to travel without medical insurance and I have been able to find a company the specialises in high-risk travel insurance – the kind of insurance used by military contractors and bodyguards – and so I have medical insurance should I become ill or the volcano gets a bit too playful, or I fall in one of the acid lakes. Perhaps reassuringly it covers me for kidnap and torture too.

But, there is no cancellation insurance. So if the political situation were to change, or the spread of Ebola moves east across the continent, or the local Afar tribe decide to deny passage through their region, or my international flight is delayed or cancelled, or I am ill then I’ll have no ability to regain any financial losses. And at just over £4000 that is a lot to lose for anyone. I am not a gambler and spend a lot of time on risk mitigation (through planning) or risk transference (through buying insurance). So this situation is definitely outside of my comfort zone – there is a very real risk of it all falling apart.

So, am I still risking it? Of course I am! I’d be crazy to pass up an opportunity to visit one of the most bizarre landscapes on Earth just because I’m worrying about what could happen. But, come December 22nd, if you see a sorry looking figure sobbing into a pint of beer in the Reading area here in the UK, you can come and tell me I should have taken the blue pill…