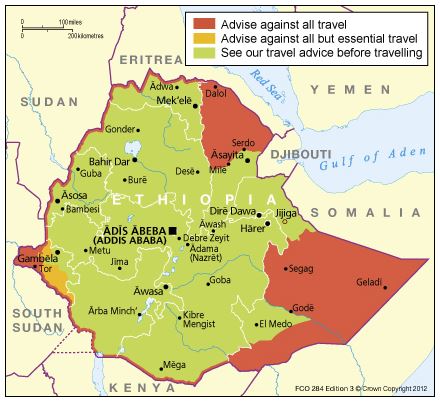

Well, with just twelve days until I leave for Ethiopia and after spending the bulk of yesterday picking and ordering the last of the clothing and equipment, most of the shopping is now complete. All that remains is the medical kit, a plastic funnel for transferring water between containers, some coloured pens and pencils and a few inflatable globes. So with all of that now done I have finally started thinking about the thing that made me want to travel to the remote Danakil Depression in the first place: Landscape photography.

Starting in Addis Ababa we’ll head east to Awash National Park before heading north and entering “No Man’s Land”

It is going to be a packed two weeks as we travel northwards from the capital of Addis Ababa up to the very top of the country and then back again along a loosely counter-clockwise route. As we travel everything will change around us: the landscape, the climate, the wildlife, the people, even the predominant religion will alter as we descend from Addis Ababa at an altitude of 2300 meters to Dallol with an altitude of -130 meters, one of the lowest points on the Earth’s surface.

For me the highlights of the expedition are the three days spent at the Erta Ale shield volcano and the time spent at Dallol. There are many descriptions of Dallol but Wikipedia probably best describes it:

Dallol features an extreme version of hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh) typical of the Danakil Desert. Dallol is the hottest place year-round on the planet and currently holds the record high average temperature for an inhabited location on Earth, where an average annual temperature of 34.5 °C (94.1 °F) was recorded between the years 1960 and 1966. The annual average high temperature is 41 °C (105 °F) and the hottest month has an average high of 46.7 °C (116.1 °F). Dallol is also one of the most remote places on Earth. In addition to be extremely hot, the climate of the lowlands of the Danakil Depression is also extremely dry and hyper-arid in terms of annual average rainy days as only a few days record measurable precipitation. The hot desert climate of Dallol is particular due to the proximity with the equator, the very low seasonality impact, the constance of the heat and the lack of efficient nighttime cooling.

For someone who is as fond of cold weather climates as I am, it will be interesting to see how well I cope with such opposite conditions. The temperature will be further exacerbated by the heat coming off the lava lake at Erte Ale whose surface temperature is a mere 1200 °C

Whilst we spend three days at Erta Ale it is, for all intents and purposes, a single environment. At an altitude of 600 metres there is little else other than the lava lake itself and the black balsaltic lava ground. Getting a good series of photographs here is likely to be as much luck as skill as we will be at the mercy of just how active the volcano is at the time, but I have a series of photographs in my head that I want to try and capture in the limited colour palette of volcanic black and lava red.

Once we descend from Erta Ale and head towards Dallol the pace will pick up dramatically and photography is going to be more of a challenge as the area offers several different landscapes with only approximately two days to capture something decent. One of the big landscapes is a salt flat much like the Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia although much smaller at only approximately 200 square kilometres. Here I’ll hopefully have a number of opportunities – from the wide vistas of the salt flats themselves to the Afar miners who extract the salt with picks, to the camel trains that take the salt to market. I may even get a chance to try my hand at salt mining in what can only be described as intensely harsh conditions.

The volcanic area of Dallol is a sight that still causes me wonder at just how such a place can exist. It is a landscape that would look at home in an old science fiction movie where they have pumped the colours to the maximum and day-glo blues, greens, pinks and yellows all mix together. Lighting here will be a key factor – it has to be right first time as there will be no chance for a revisit.

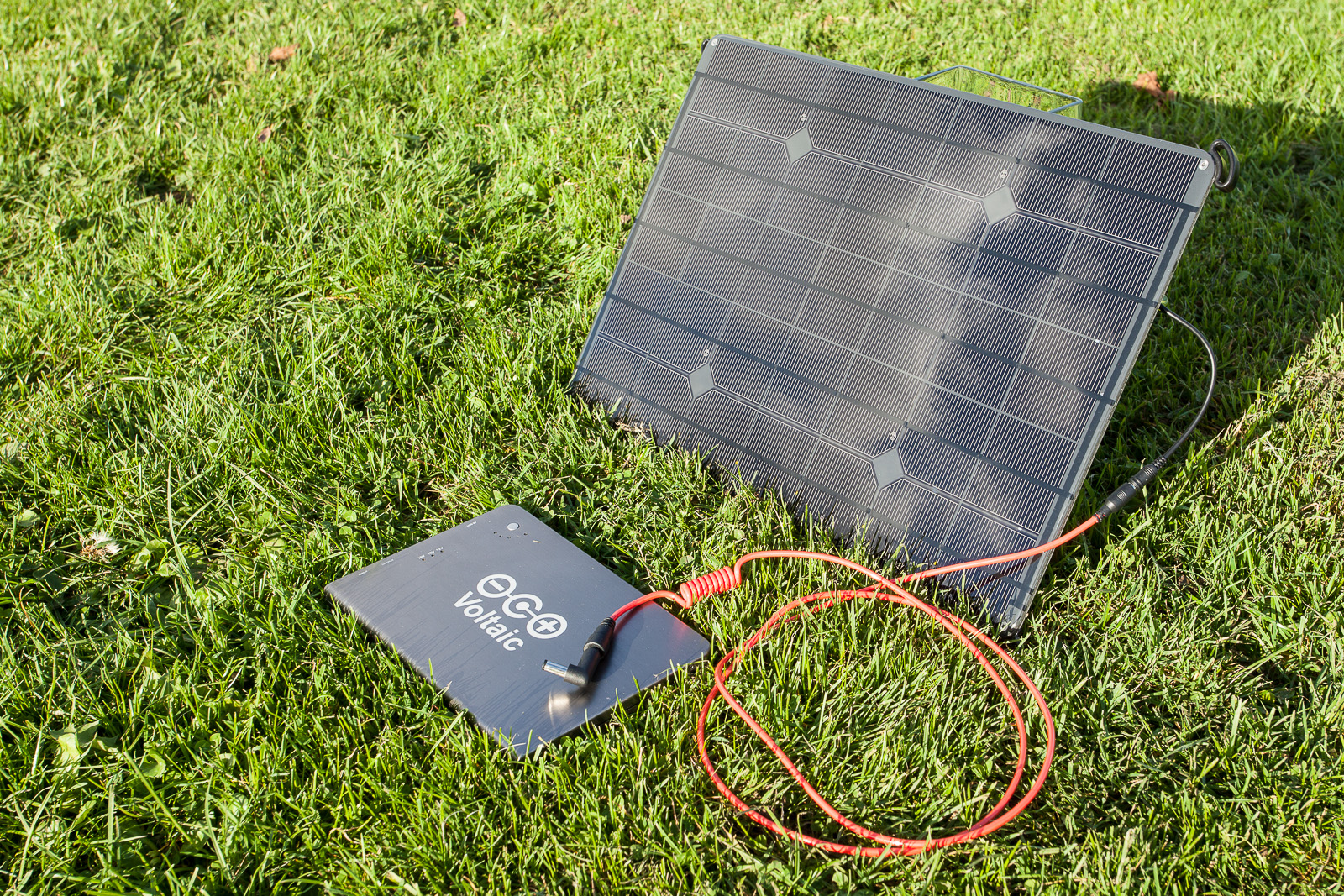

Another thing that I want to try whilst in the Afar region, and particularly the Danakil Depression itself, is astrophotography. It is not a style of photography I have any experience of and involves its own set of rules and techniques that I know very little about. But the one thing that every astrophotography web site and blog I have visited agree upon is that astrophotography works best when there is no light pollution to obscure the incredibly faint light from distant stars.

Yellow is light pollution and blue is darkness: Jazan on the top border is typical of towns and cities. In the northeast of Ethiopia we’ll have no problems with light. The only light sources are from lava.

Looking at the above image from blue-marble.de – a web site that shows satellite imagery of light pollution across the planet – it is easy to see why the one thing I can guarantee is that – in what Wikipedia and National Geographic call one of the most remote places on Earth – light pollution will not be a problem.

So I have given myself a crash course in astrophotography which in turn has led to having to learn the basics of how to locate and identify the constellations and navigation by the stars. I am hopelessly under-prepared but there is not much I can do now other than make use of the location and hope that what little I have learned will help me produce something I like. Unfortunately however, whilst I would love to take a photograph showing the Milky Way galaxy in the night sky, I believe I’ll be there at the wrong time of year. On the plus side however, to capture some really rich star field images, even the moon can be a problem and most recommendations suggest shooting on nights leading up to and immediately after a new moon. As I start the expedition on the 21st December – the day of the new moon, I’ll have ideal conditions to shoot the night sky – assuming it is not cloudy, that is.